|

|

|

|

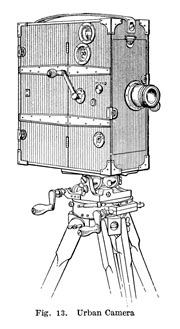

The Wisconsin Bioscope Company takes its name from the camera used to

make the company’s first picture in 1999, a Bioscope Model D, made in

1907 or before by Alfred Darling for the Charles Urban Trading Company.

Darling was an engineer in Brighton, England, who made all sorts of

cinema equipment before the First World War, especially cameras for

British equipment retailers such as Williamson, Wrench, Prestwich, Moy,

and Charles Urban, an American active in the British market. The Bioscope Model D has two drive sprockets, one for film supply, the other for take-up—unlike Louis Lumière’s master sprocket design. This makes possible a through-the-lens viewing system via a tube running from a glass pressure plate in the gate clear through to the back of the camera. The camera has three crank sockets—one turn eight frames forward, one turn eight frames reverse, one turn one frame—and a supply of special aperture masks—binocular, keyhole, etc. Although Wisconsin Bioscope produced two brilliant films with this camera, its technical limitations soon became apparent. It requires a lens with a focal length of at least 75mm, a moderately long lens necessitating a large studio. The camera’s gear train is complex and elderly making it hard to crank. It also produces non-standard framing. |

|

| The Urban Bioscope Camera illustrated in The Cyclopedia of Motion-Picture Work (1911). |

The Wisconsin Bioscope Company used this camera to film Plan B (1999) and Winner Take All (2000). |

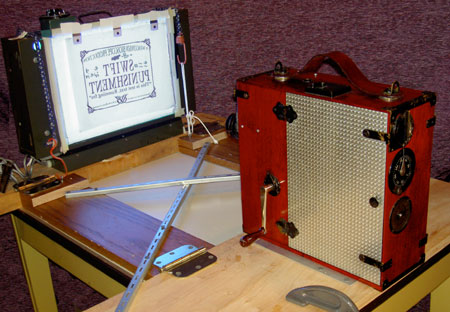

| Realizing the limitations of the Bioscope camera, the Wisconsin

Bioscope Company obtained a Universal camera, manufactured in Chicago

sometime after 1923. As can be seen by its front nameplate, this camera

was once used for newsreel work. It is more mechanically sophisticated

than the Urban Bioscope camera and smoother running. It has become the firm’s main tool, not

only for taking scenes in the studio or in the field, but also for

shooting titles. The Universal camera has the same general layout as the Bioscope, but it is smaller because thin aluminum was used instead of thick mahogany. Like the Bioscope, it has through-the-lens viewing, but because it has a master sprocket behind the aperture plate, the light path is diverted to the right side of the camera by a prism. Like the Bioscope, it has a supply of aperture masks, but whereas the Bioscope’s film door and gate had to be opened to fit a mask, the Universal’s masks can be exchanged from the exterior without fogging the film. The Universal camera has a variable shutter that can be operated from a control on the back of the camera and an automatic shutter dissolve control which allows for accurate and repeatable fade-ins, fade-outs, and lap dissolves. While an improvement over the Bioscope camera, the Universal also has problems, mostly concerning its viewfinding system which maddingly does not truly indicate accurate framing or focus. |

|

|

|

| Wisconsin Bioscope’s Universal camera in position to shoot titles in 2007. |

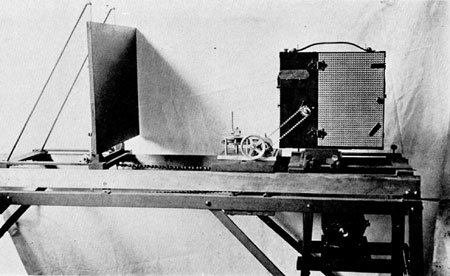

A Universal camera being used to shoot titles in the 1920s, from Carl Louis Gregory’s Motion Picture Photography (1927). |

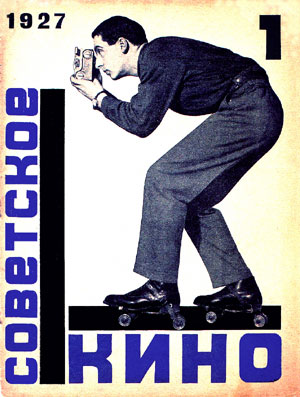

| The Wisconsin Bioscope Company also has a

Debrie Sept camera from the mid-1920s. This is a small spring-wound

35mm motion picture camera that holds 17 feet of film, yielding just 17

seconds of action at our normal rate of 16 frames a second. Septs were used by newsreel cameramen to take surreptitious pictures when cameras were forbidden and by Hollywood studios for special shots requiring ultra-small, ultra-portable cameras. It is said that Abel Gance used Septs while making his 1927 epic film Napoleon. They were also used by Alexander Rodchenko and Dziga Vertov in Soviet Russia. |

|

|

|

| Wisconsin

Bioscope’s Debrie Sept. The camera was named the Sept because it had

seven functions, based on the various combinations of its ability to

make still as well as motion pictures and function also as a projector

and printer. |

Varvara Stepanova’s cover design for Sovetskoe Kino.

The man on roller skates with the Debrie Sept is Mikhail Kaufman,

Dziga Vertov’s brother and cameraman. In 1925 in Paris, Alexander

Rodchenko bought two Septs, one for himself and one for Vertov. |

|

The last camera in Wisconsin Bioscope’s panoply is the Ernemann

Aufnahme-Kino C II made in Dresden, Germany, in 1916. It is a small and

simple camera with a rudimentary external viewfinder and a capacity of

about 100 feet of 35mm film. Alas, it lacks a crank and lens. Perhaps you who read this have these missing bits in your possession? If so, we would be most pleased if you would send them along to |

|

|

| The Ernemann

Aufnahme-Kino C II (1916). |

|

|